No, I’ve not changed my plumage or species affiliation (yes, there is a Green Jay). It’s more in the human sense that I’ve “gone green”. I’m now harvesting most of the electricity my house uses from what falls on the roof.

What it is

How I’m doing this is with a grid-tied solar power system. This consists of a bunch (26) of solar panels on the roof to collect energy from the sunshine and convert it to DC electric current (kind of like what you get from a battery, but up to around 400 volts), two inverters in the garage to convert that to AC household current, and an electric meter that measures power going both ways, to and from the electric company.

Because we’re still tied to the electric grid, we can draw power from there when the solar panels aren’t producing enough power for our needs, like at night or when it’s too cloudy. At other times, when we’re producing more power than we need, our excess flows back into the power grid to help power our neighbors. Through the magic of “net metering”, we get credit for any power we push back up the line, and only pay for the “net” usage; that’s why we have the electric meter that records power going in each direction. Not all electric utilities do this, and some don’t credit power you send them at the same rate as what they send you, but Laurens Electric does.

Getting the project going

I actually started this process back around the beginning of 2014, but things got sidelined last year due to a family member’s medical needs. I started by contacting a number of installers in the area that I google’d up, getting quotes and reference lists, checking BBB, etc… I awarded the job to Sunstore Solar in Greer, SC because they’ve been in business a good while, I’ve seen their people in the media (so I had no qualms about them being who they say they are: always a concern when you meet people via the Internet), and they were very accommodating of my constant questions and delays (one installer I was communicating with just stopped returning my Emails).

The project went through several iterations, but we settled on an 8.5kw (that’s the amount of power that can be produced at any given moment, best case) system, which should just about cover our needs based on my electric bills.

I had another delay while the roof got re-shingled. I didn’t want to put a bunch of 25-year solar panels up on a roof that was already 16 years old, so that had to be done first.

The total cost of the project (not including the roof) came to just shy of us$40k. That’s a big chunk of change, but tax credits will return more than half of that. I just have to wait on the next couple years’ tax refund checks. Taking that into account, and the savings on my electric bill (over the course of a year, the solar power should cover almost all of it), we should break even after around 8 years, and after that, for the rest of the 25 year life of the system, it’s all savings.

The money is just one reason I did this, of course. In fact, in business, an 8-year ROI (Return On Investment) would probably get nowhere. Getting power from just what falls on the roof, with no carbon or nuclear, is the other big reason. Now, I realize that my paltry few mega-watt-hours ain’t gonna even show up on the digital readouts at the power plants, but, like a lot of things, ya gotta start somewhere. As more and more of us do this sort of thing, we will make a dent in the environmental impact.

Installation

The installation began on 8-June with the arrival of two trucks worth of installers and parts. Some of the guys started on the roof, marking out where the panels would go, while the rest of them went to work in the garage installing the inverters and all the wiring to hook it all together.

Before long my roof gained a set of pimples:

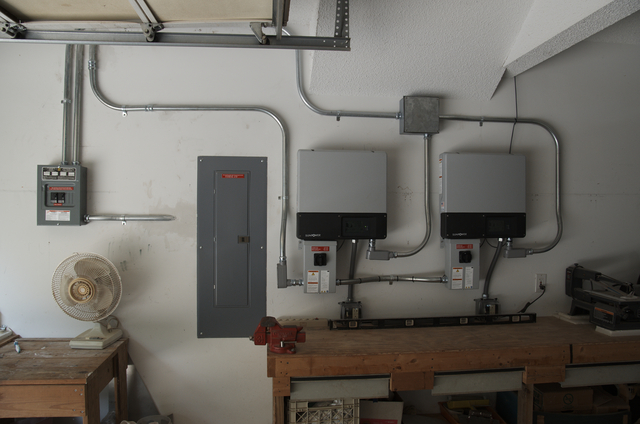

and the garage got covered up with conduit:

A note about what all that conduit is for: one has the wires bringing power down from the solar panels themselves, and going to each of the two inverters, connecting at the bottom of the disconnect switches below the inverters on the right. From there, another set of wires carries the now-AC power over to the small electrical panel on the left. There the output of the two inverters is combined. Then that has to be fed to a disconnect switch on the outside of the house, before coming back in to the main household electical panel.

Because this is a grid-tied system, there has to be a ready way for utility workers to disconnect the system when they have to work on their lines and equipment. They can shut off the power from their end, but they need to be able to ensure that no power is feeding back the other way, which can be a hazard to the workers. The inverters are designed to detect when utility power shuts off and to shut themselves down automatically, but having worked in a lock-out/tag-out environment (where energy sources have to be secured and locked out for safety), I understand the need for a way to ensure that, yes, this wire is really dead and will stay that way.

Anyway, back up on the roof, the racks that will hold the solar panels go up:

and then the solar panels themselves;

According to the spec sheet, those panels weigh 18.6kg (41 lbs.). Yeah, those guys worked hard to get this done.

Eventually all the panels made it up on the roof.

Not being one to be up on a roof myself, I understand why they had all those ropes there. The guys working on the roof were very careful to stay tied off, and it paid off as no one fell off. That would have thrown the whole project off.

By the end of the 3rd day, everything was installed, the area had been cleaned up, and a brief “smoke test” had been accomplished.

Now we had to wait on the county building inspector to come and inspect. That happened on Friday of that week, and didn’t take long. Actually, most of the time was spent by me pointing out the components and what they did. I suspect that the inspector had prior experience with these guys’ work, and knew just what he was looking for. He said it was all “neatly done”.

The last hurdle was Laurens Electric. I was thinking that, since this is a co-op, I own it and could just call ’em up and make it happen, but that wasn’t necessary. Once they got the report from the building inspector, they came out and changed the electric meter. That happened on Tuesday of the next week.

A couple days later the SunStore folks were back to formally commission the system on 18-June, which included connecting the inverters to my network so they could report back data to the manufacturer’s (SunPower) site, where I could monitor the operation and production. When we built the house, I was smart and put a network drop in the garage. Unfortunately, I put it on the opposite side from where the inverters ended up.

I said that the solar power shuts down when utility power goes off, but the inverters I put in do have a provision to provide power via a separate circuit directly from the solar panels in that event. This can be used during an extended utility outage to run a refrigerator or charge phones, so long as the sun is shining. Those outlets are mounted right below the inverters.

Early results

So far, the system is performing to expectation. With the current heat wave and running the air conditioning almost all the time, we’ve been getting a bit over half our electrical power from the solar panels. As the weather cools off, I expect that will increase, even though the days will be getting shorter. In fact, we had one day when the heat wave broke (briefly) and with cooler temperatures (mid-80’s F) and good clear bright sun, we got 92% of our power right from the sun.

There’s nothing on the inverters that’s accessible from the local network by default (they just talk out directly to the manufacturer’s portal), which is a good default setting (too many equipment manufacturers don’t even give a first thought to security), but after doing a bit of research, I found that they will speak modbus (a protocol used in industrial control and building management systems, and which I just happened to be familiar with due to my work around the data center) if you turn it on using the manufacturer’s software (SunnyExplorer). So now I’m able to read data directly and add it to my weather web site on my The Sun page. You’ll probably notice that you don’t see the green “Inverter 1” line on the graph. Both inverters have the same configuration of solar panels, so they’re generally almost identical in output and the two lines lie right on top of each other.

You can too

If you’re interested in doing this sort of thing, I suggest you contact some installers in your area. Each situation will be a bit different: different electrical loads, different siting, different financing… It would be good if you could provide a year’s worth of electric bills, or at least the kWh and cost, so they can design a system to meet your needs. Do check the specs carefully on any proposed system: at one point, I had two quotes where one was double the other; turned out that the cheaper one was also 1/2 the capacity of the other.

The future

Right now we have gas heat and hot water; everything else is electric. The next project is going to be the HVAC, and I’ll be looking into something more like a heat pump with gas backup, rather than just straight gas heat. I’ve got room and inverter capacity to add several more panels to cover that if needed.

One thing I wonder about is how we’re going to pay for all the wires and equipment that makes up the electrical grid. Ultimately, if we all put solar panels on our roofs, producing enough power for each of our needs, and if net metering continues as we have it here, there would be no money going to the electric companies because our “net” usage would be zero. Yet we’re still using the company facilities to keep us suppled when the sun isn’t shining. Maybe the way some utilities reimburse for power (different rates for what they provide vs. what you provide) is the answer, or maybe just some fixed fee for being connected to the grid. I’m sure they’re thinking about this.

Another technology that’s coming into play is batteries. Tesla recently cannon-balled into that market with household batteries to be used with renewable energy sources. Theoretically this can enable you to completely disconnect from the grid if you have the generation capacity to store enough power during the good times and battery capacity to get you through the bad times.

Some time when I get an ambition attack, I’ll put another network drop in the garage by the inverters and eliminate that cat6 wire stretched across the ceiling.

Conclusion

I’ve been wanting to do this for a long time (at least since before my Sister put up solar panels several years ago – sibling rivalry?). Finally, I’m there, and I’m glad I did it. I was taught to not leave a mess, and I’m hopeful this will help clean up some of the mess my being a productive member of this society has caused.

I think I begin to understand, just a bit, what it must be like to be a farmer. The farmer’s crops, and my power production, are at the mercy of the weather. When the clouds roll in and I see that wattage drop to next to nothing, well, there’s not a darn thing I can do about it. But the sun will shine again :).